You’re reading a free edition of What They Said newsletter, which goes out once per week. If you upgrade to a paid subscriber for $6 per month, you will not only be supporting this project, but you will also receive weekly issues of this newsletter. Substack provides me, as a writer, an alternative means of publication.

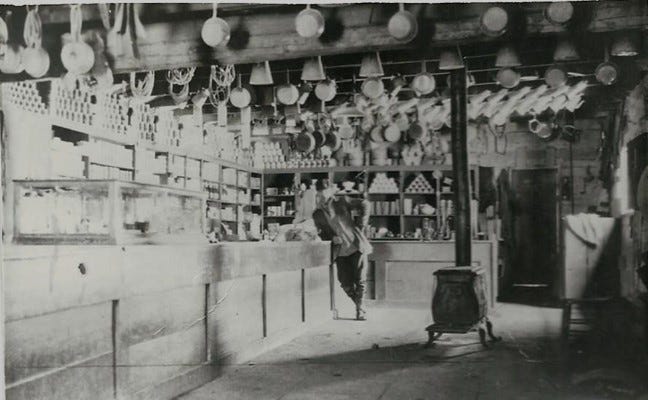

George E Kennedy Sr – 1916

Traders and the Navajos were always hand-in-glove in every aspect of their lives. What affected one also affected the other. That included not only regulations, but opportunities as well. While those opposed to traders were always looking for flys..t in pepper, the traders sought opportunity for the Navajos. The Navajos had no jobs and no leadership until the 40s. The traders were essentially their guardians. Several different warrior clansmen such as Narbona and Manuelito represented certain clans of Navajos. Chee Dodge was a recognized leader and became official in 1942 when he was elected as Chaiman of the Navajo Council. The Navajos were wards of the US government and as such were “watched over” by agencies of the government. Chee Dodge’s election didn’t change all of the bureaucratic direction, but finally the Navajos had a voice of leadership after 100 years.

Like most of the southwest, Navajo country has an abundance of piñon trees. They are nut-bearing, short-needle trees similar to pine trees. Piñon nuts, the size of pinto beans, have always been a delicacy for southwest people. The piñon crop occurs each fall beginning in September and continuing to the first heavy winter snow. The abundance of the nuts is determined by summer moisture. If the moisture is inadequate, the trees will blight. Because of the vast amount of Navajo land there are always certain areas that will yield a crop.

Piñon Nut Cone

Until 1938 there was no concerted effort to harvest and market piñons from the reservation. Navajos had experience and skill for harvesting, but lack of marketing restricted them to only personal use. The nuts were picked from the ground after the cones opened at the first frost.

Growing up among the Navajos, Dad recognized the significance of piñons as an important opportunity. In 1938 the Agress Nut Company in New York retained Dad as an agent for them to develop the piñon market. Dad became an expert on piñons. Agress agreed to purchase at least 500,000 pounds of piñons a year, depending upon crop size. The nuts were popular with the Italian communities on the East Coast for use in pesto. At the time piñons were valued at 8ḉ per pound and remained so for a number of years. Dad organized harvesting by coordinating Navajo pickers and traders. Most Navajos could pick at least 20 pounds of nuts a day and were paid per pound. After several years Dad went his own way with an Agress agreement to purchase at least 500K pounds per year. Over the next ten years he developed supply relationships with nut companies in El Paso, Los Angeles, and Denver. Annual harvesting became a Navajo tradition. More importantly piñons created a significant economic benefit for the Navajo people because it was a cash crop.

Dad recognized both a business opportunity and an opportunity for the Navajos who had little or no income opportunities.

John Wooden - UCLA Basketball Coach

“You cannot live a perfect day without doing something for someone

who will never be able to repay you”.

Handling and storage were major drawbacks from the outset because the nuts retain moisture, and a crop could shrink up to 10% in a few weeks. Initially communication was also a problem. Dad coordinated everything from Gallup. If a major crop occurred in the Grand Canyon area, as it often did, he depended upon radio stations to relay crop news. Two main radio stations in Gallup and Holbrook, Arizona had wide-ranging, regular, daily programming in Navajo and the people were accustomed to the broadcasts for news and events. Two things were important in piñon communications, crop locations and weather. There was no phone contact between Dad and harvesting efforts. He always maintained a buying location in a major, off-reservation crop area, such as the Kaibab National Forest, that had no “resident” trader. He never abused trader relations with their customers, especially with Navajo rugs.

One year in the 50s, a heavy crop in the Grand Canyon area was about to encounter heavy snow. Dad could not get word to his buying location without driving four hours to deliver his message. The Navajos were already aware because of the radio. By the time Dad got to his buying location the flood of nuts had begun and most pickers had left the area to return home where they would sell their nuts to their trader. That year Dad went to storage with 3 million pounds of piñons.

Storage of piñons can be a risky business. Because of the moisture content of the nuts, they could shrink up to 10% in weight in the first 10 to 30 days. If stored, they had to be in a cool warehouse and the inventory had to be regularly rotated. I can only imagine the work in rotating 3 million pounds.

I learned the piñon business as I did the trading business, by accompanying Dad. Each year in July we would begin surveying crop opportunities as we drove the rez trading for Navajo rugs. We would cut small cone-bearing branches and follow cone development each month in potentially high-yield areas. The Navajos knew their areas and early on would start telling traders of an impending crop. Primary concern was the amount of rain in the areas. We had weekly conversations with traders that included yield projections. As the crop evolved, traders would provide anticipated needs and we would offer our projections and our customers’ pricing tolerances. Most people failed to recognize the relative insignificance of piñons in the total nut industry. We had to be conscientious of all aspects and keep a balance of pricing fairness in the trade. In a good year, our customers would commit to at least a million pounds. In turn we maintained regular contact with trading posts. From 1950 to 1960 the price of piñons rose from 8ḉ per pound to $1 and finally$3. That price remained fairly stable until the late 80s.

As we observed crop development, we coordinated with traders. They were important to our supply chain because most of their customers picked in other areas and returned home with their harvest. There was always initial concern among traders about pricing. Piñons were always a cash crop, and most traders couldn’t risk being out of position on pricing. They depended upon us to set the price. In turn we provided a weekly price guarantee for anticipated trader accumulations. If a large crop threatened a trader’s cash position, we advanced funds for them. If a trader sold a load against our guarantee, they lost the guaranteed opportunity for the remainder of the season. A trading posts could typically buy between 200 and 5,000 pounds per week.

I always handled most of the tonnage myself and Dad maintained contact with our customers and traders. In the late 80s as we anticipated another crop, I mentioned that the bags were getting very heavy. Because of the cash involved it was important that Dad or I handled the transactions. Hearing our discussion, Mom interjected, “You are like fire house dogs. When the bell rings you respond no matter how tired you are”. She was right.

Piñons ready to ship

We shipped piñons every week because of shrinkage. 18-wheel semis could haul 40,000 pounds and railcars 80,000 pounds. It was an exhilarating time for us. Our ass was hanging over the edge for several months each year. Shrinkage on 40,000 pounds could be significant since we worked on slim margins because of our high volume. Much like Costco selling an item for significantly less than a convenience store.

Dad always did the phone work, and I did the road work. Dad was in constant contact with the traders and our customers. He was always aware of the Navajo pinon market with major suppliers who were constantly tempted by foreign imports. He had to protect the Navajo market. He tracked down rumors that were always in the wind usually dealing with orders and pricing. A trader might get a call from a competitor that one of our customers was waffling and causing a drop in the price. A 10ḉ drop in price could cause concern for a trader if he was sitting on several thousand pounds. The traders would immediately call us to be sure that their price guarantee was still in effect. Dad would always be confirming shipments and customer inventories. He would call ahead to the traders with my projected arrival times. If I needed to check in, he always left a message with a trader on my route. Sometimes a trader would say that he had a higher offer than what we were paying. We had to remind them that if they sold out from under us, there would be no more guarantees for the season. These issues usually came from store managers, not owners. Several times, if we quit buying, stores would accumulate inventory that took months to liquidate.

It is interesting to look back and wonder how different the business would have been with cell phones.

Each day from early October until the first heavy snow in December, I left Gallup early in the morning driving a truck capable of hauling 25,000 pounds of piñons. I also carried a platform scale, burlap bags, sewing warp, needles, and a case of Zuni jewelry for rug trading. We got bags from bean farmers in southern Colorado. Each bag could contain 80 – 85 pounds of piñons. The Navajos gathered piñons using Blue Bird flour sacks. Each sack could handle ~20 pounds, so the burlap and flour bags provided a good reference for weight. If we spoke with a trader about his piñon inventory, we always spoke in terms of bags. 20 bags would be about 1,600 pounds. If a bag was heavier than usual, it usually had some rocks added for weight. Sometimes I had to re-sack to better manage my load. One store, Cross Canyon Trading, was small store near Ganado, Arizona. The trader, John Barr, knew the importance of piñons to his customers and stayed open seven days a week until nine or ten pm so that his customers could sell their piñons and get groceries. His store was about 50 miles from Gallup and most weeks his volume was such that I made a special trip just for him. We communicated regularly about his inventory. If I was returning with a load, passed his store, and had some room on my load, I always stopped to keep him cleaned up and in good cash position. Every time I had to spend time sacking piñons because he dumped them into boxes and barrels and returned the Blue Bird sacks to his customers. It was always a lot of extra work, but John was a hard-working guy and did all that he could to accommodate his customers. I never minded the extra work.

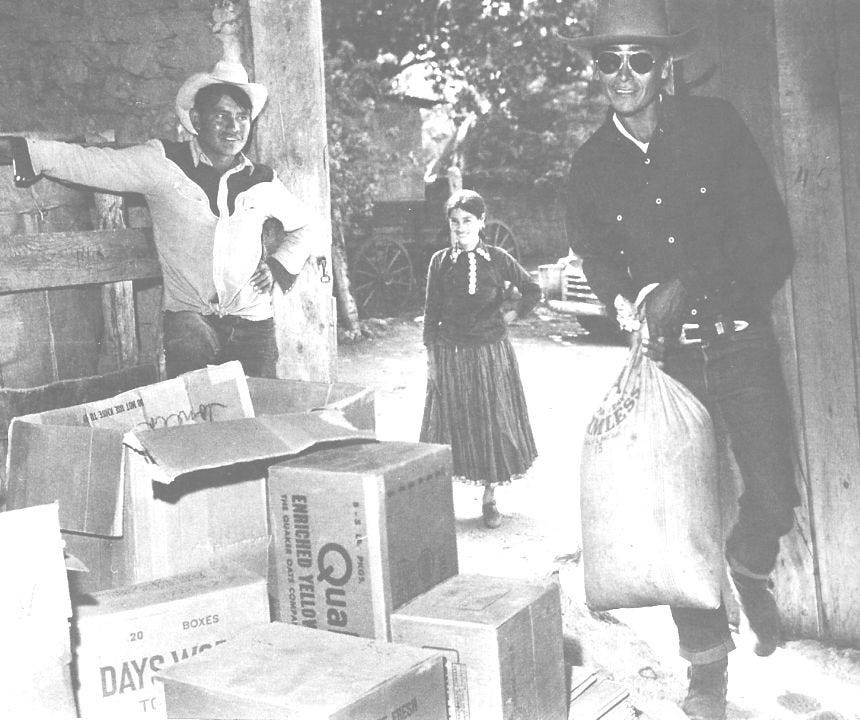

Buying piñons at Cross Canyon Trading Post

On trips to the western part of the rez, I would often divert to Flagstaff and unload at Anderson Trading. The store was affiliated with Mayflower Van Lines and located on a rail spur. We could make truck or railcar loads from there.

Each night I would return to Gallup and unload for the next day. Loading and unloading 25,000 pounds of piñons was a workout! We regularly shipped by both rail and truck. Our silversmiths were enlisted to help with loading.

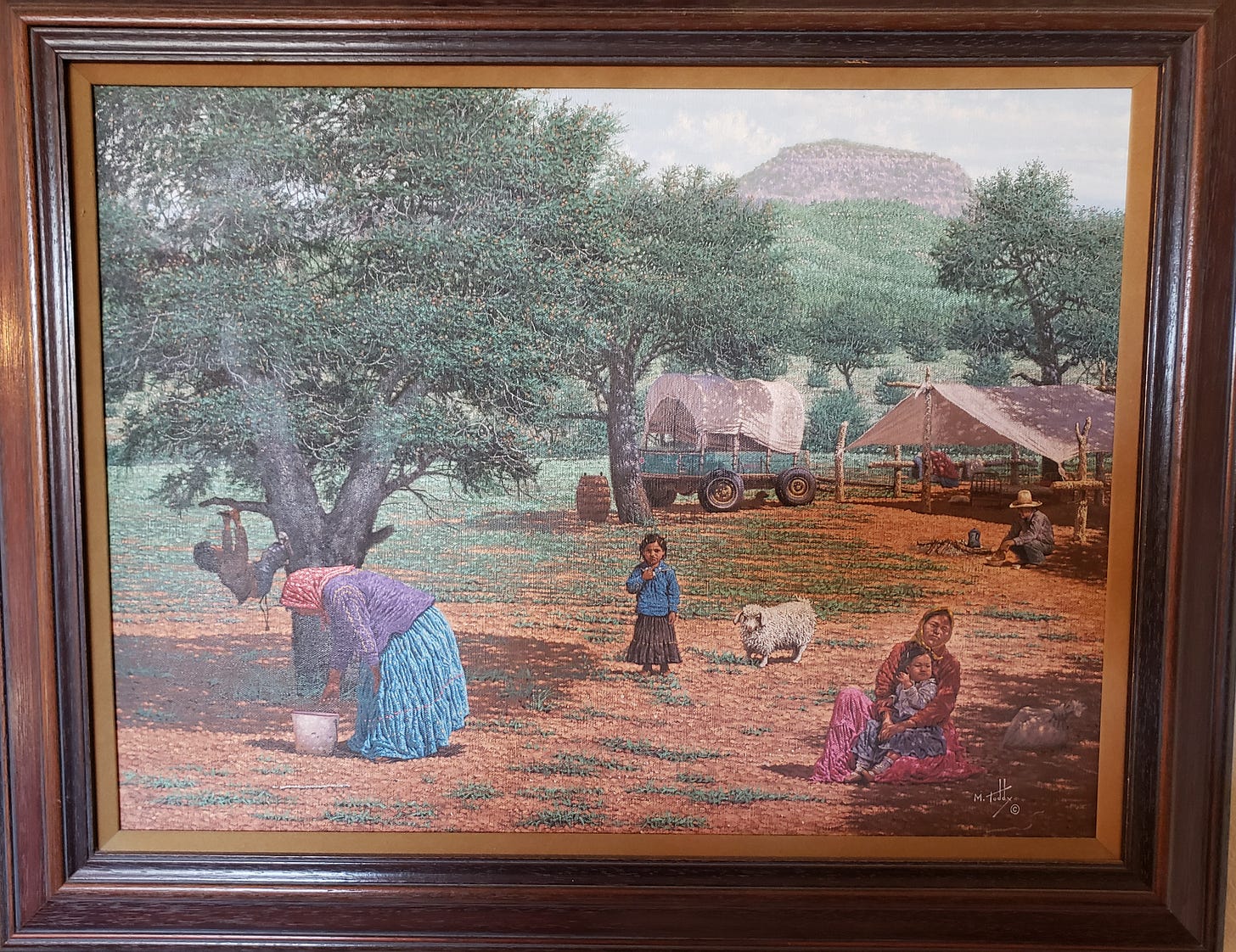

One year I set up a buying station in the local mall where we had a sports shop. The main crop was the Grand Canyon area, so I ran buying ads on Holbrook radio. Within days people lined up with their piñons. As I was working one day, the well-known Navajo artist, Marvin Toddy, stopped to see what I was doing. He was a good customer at the sports shop. He commented that he had never done a painting on piñons. I mentioned that if he ever did, I would like to have an opportunity to buy it. On Christmas Eve we were having a staff party at the sports shop. There was knocking on the back door. Marvin wanted to tell me that he had completed a painting. I slipped out the door to have a look. Someone saw us and proclaimed, “Marvin has a painting”. Everyone poured out of the store to have a look as I completed the purchase. I took the painting from Marvin and handed it to Sheila with a “Merry Christmas”.

Marvin Toddy painting of a Navajo piñon camp.

Piñons can be eaten either raw or roasted. I always preferred roasted because of health safety. In 1995, there was an epidemic of hantavirus, a severe respiratory disease, in the southwest United States. It especially impacted Navajo people. Public concern was such that people crossing New Mexico on Interstate 40 would not stop in Gallup.

Piñon nuts are gathered by rodents, particularly rats and squirrels. In their process of storing many rodents urinate on the nuts. Many nut-gathers used to raid the nests of these rodents.

Gallup has the largest public health hospital in the US. It was established to serve the large surrounding American Indian population. A local PHS physician, Dr. Bruce Tempest, after exhaustive research confirmed that piñons were the vehicle of hantavirus because of rodent urine. Navajo people usually don’t roast their piñons for personal use.

I recommend roasting piñon nuts. To do so:

1) Wash the nuts with boiling water

2) Let the nuts dry on a towel

3) If you want salted nuts, rinse the nuts again in heavy salt water

4) Again, air dry on a towel

5) Put the nuts on a baking sheet with parchment paper because the nuts may have piñon pitch that will melt.

6) Turn oven to 350°

7) After ten minutes begin checking the nuts. When you detect a roasted flavor, remove the baking sheet and put the nuts on a towel. They will continue to cook because of the hot shells.

8) If roasting for the first time, consider starting with a cupful. Prices are such now that you don’t want to burn the whole batch.

I ate them by putting a handful on one side of my, cracking the shell, Spitting it out and chewing on the other side. I was as good as a squirrel! Perhaps TMI, but people always ask me about roasting piñons.

Dad and I retired from the piñon business in the mid-90s. The market became tumultuous without the stability of a reliable market, pricing, and coordination among traders and major outlets. Most traders had nowhere to go for market information or sales. The large nut companies weren’t interested in small lots and were reluctant to pricing commitments. Pricing became arbitrary ranging from $7 to $15 per pound. A 20-pound bag of piñons was theoretically worth $140, and a truck load could be worth $280,000. That was unrealistic and unsustainable. In the chaos the large piñon customer, Azar Nut Company in El Paso was purchased by FritoLay and that changed the marketing scheme of the company including the discontinuation of piñons. Now piñon nuts are available in specialty retail shops, flea markets, and corner vendors. My sense is that the market today is less than 10,000 pounds, compared to our times of 500,000 pounds.

Once again, the Navajo people were lost in the shuffle. They were the largest segment of our US population affected by hantavirus. In 2020 the Navajos were again slammed by the COVID pandemic. They were again the largest per capita victims in the US and Gallup’s county was the focus of their issues. People throughout the US were impacted by the conditions imposed by the pandemic. None more than the Navajos – once again in their history. Standstill from the pandemic opened the door for imported pine nuts from China and that effectively killed piñons, rising prices notwithstanding.

We were the major factor in maintaining pricing stability with piñon nuts because we participated in all sides of distribution and worked on slim margins. That was important to the ongoing piñon market. Piñons had been a great Navajo economic activity for nearly 60 years. We made money, the traders made money, but most importantly the Navajo people made money. It was a niche business specific to the Navajo people.

Next week: Special people in my life

Next week - Special people in my life