06272025

In 1913, my grandfather moved his family to the remote Navajo reservation and built a trading post and family home. For the next 25 years, he lived with the Navajos. Unlike other North American traders, Navajo traders lived with the people. In most instances, the traders' only friends and neighbors were trading customers and their families. The Navajos spoke no English, had no money, and had no jobs, hardly stimulating conditions for success. All business was done with trading. Thus began a family legacy that spanned over one hundred years and three generations. I was part of the third trading generation beginning at age nine. Except for college and a brief corporate career, I was in the trading business for most of my life. The trading business has provided me with unique opportunities and experiences.

Until traders came to Navajo country, the Navajos traveled by foot or horseback, but the only “traveling” that they did was herding their sheep; the men went hunting and their trips to their trading post. There was no place or reason for them to travel, despite having a reservation the size of West Virginia. Until 1920, there were fewer than thirty trading posts throughout the reservation. By 1950, there were 250 trading posts, and 70 of them were within 50 miles of Gallup.

Horses were introduced to the Navajos in the late 1600s, and they were primarily used for hunting and raiding. Most families did not have a corral of horses.

A story tells of a Navajo man and woman together. The man is on horseback, and his wife follows behind him on foot. The man is asked, “How come you are on horseback and your wife is walking?” He replies, “Because she doesn’t have a horse.”

Trading posts facilitated Navajo mobility by providing them with a destination and a purpose. Since they are semi-nomadic people living in family units, trading posts provided a place to socialize as well as trade. A trip to a trading post was usually on foot or horseback and was an all-day affair. They would return with goods that they could carry.

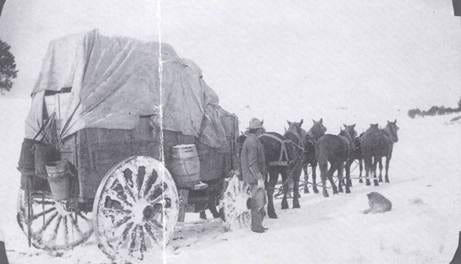

Traders received merchandise and sent trader goods to their supplies by wagon. Each trading post had access to a freight wagon, driver, and team of horses, usually six. My grandparents were 98 miles from Gallup, which was a two-day ride. Their supply wagons could only operate between May and October because of snow and mud. The round trip of a freight wagon was ten days. It took three days to reach Gallup, and three days to load the wagon and rest the horses, and four days for the return trip with a heavier load. Along the way, the wagon would stop at Hubbell Trading and load barrels of water for Cross Canyon trading, which did not have an adequate water well. On the return trip, empty barrels were dropped off at Hubbell’s. Each way, the driver would spend the night at Cross Canyon.

The Gallup Merc had a large area of several acres to accommodate the horses and camping facilities for the drivers. As Navajo families began coming to Gallup by wagon, they would use the same area.

If the wagons traveled along a highly traveled road, they would use a road next to the highway for the wagon traffic.

Because of the winter season, Salina Springs (Granddad’s trading post) could not receive merchandise. For several months before the October cutoff, orders had to be steadily increased to build winter inventory.

In 1913, the last wagon of the year left Salina for Gallup, and winter weather came early. The wagon did not return for 35 days. The driver had to survive on food from the load.

In my book, A Good Trade, my grandmother wrote, “I cannot imagine how the Navajo people in our area survived winters before George opened the trading post.”

When granddad went to Chinle Trading, he had a wagon team and driver, John Gorman. John was steady as rain and worked as a clerk as well. John’s brother, Carl, was a Code Talker in WWII and later became an accomplished artist, followed by his son, RC Gorman.

Trading posts offered wagons for trade. Traders encouraged the use of wagons for transportation and trade.

The first wagons were Studebaker Wagons, and they became a mainstay for Navajos. The trading posts would receive wagon “kits” from their suppliers and then assemble the wagons.

The wagons could be accessorized with frames and covers. To facilitate pulling through mud and sand, some families retrofitted car axles and tires.

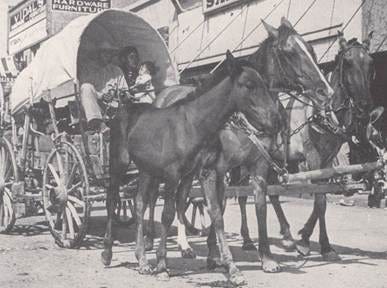

A Navajo family leaving the trading post with their supplies.

As a boy, I remember seeing Navajo families drive their wagons through town.

If a mare was part of the team and had a colt, the colt walked alongside, untethered.

A Navajo family passed by our home in the early 50s.

Each August, the annual Intertribal Indian Ceremonial brought many wagon families to town. Many set up camps with their friends along the perimeter of the Ceremonial grounds. At night, the sounds of their singing, chanting, and drum beats echoed through town.

During the Ceremonial parades, local kids were invited to sit on wagon tailgates and ride through town with the Navajo families. Along the parade route, businesses would provide free merchandise for the wagons. Watermelons were very popular. I remember watermelons selling for a penny per pound for years.

The Ceremonial grounds had a 1½ miles oval track. A popular event was the wagon race among Navajo women. Each contestant began by building a fire before getting in her wagon.

The racetrack also included foot races among the tribes. Each tribe would send a relay team that circled the track several times while kicking a stone ahead of them, barefoot. It was no surprise that Gallup High School won the State Cross-country championship for twelve consecutive years in the 70s and 80s.

After WWII, soldiers returned with a broader world perspective and money. Trucks became their primary transportation, and the Navajo people became more mobile. Wagons began to diminish. For years, Gallup had the largest Chevrolet, Ford, and GMC truck dealerships in the US. The saying was that Navajo trucks had a warranty of 50,000 miles or 50 days, whichever came first. Trucks became a trade item for us with the Navajo traders. We would provide a trader with a new truck and receive rugs as payment.

In my generation, our trading activities had changed from wagons and horseback to computers and planes. The changes occurred within thirty years.

What They Said newsletter goes out once per week. Substack provides me, as a writer, an alternative means of publication to supplement six books that I have written; four about southwestern culture that include American Indian trading, of which I am a 3rd generation trader, a major tribal ceremony, and a prominent Navao artist biography. What They Said is a collection of quotations that I have accumulated for 65+ years. Thus far, I have prepared and scheduled weekly postings through September 2025. If you wish to become a paid subscriber, there is a choice of rates: $6 per month or $60 per year to support this project. Thanks.